Dell Duval has been living on the street since his accident. He can’t remember who he was or where he came from. All he has is a tattered note in his pocket with an address for the Ellis house, a sprawling, ancient residence in Jacksonville. He doesn’t know why he’s been sent here.

In the house, Lane and her son Theo have returned to the ancient family home—their last resort. The old house is ruled by an equally ancient trio of tyrannical aunts, who want to preserve everything. Nothing should ever leave the house, including Lane.

Something about the house isn’t right. Things happen to the men and boys living there. There are forces at work one of which visits Theo each night—Mormama, one mama too many.

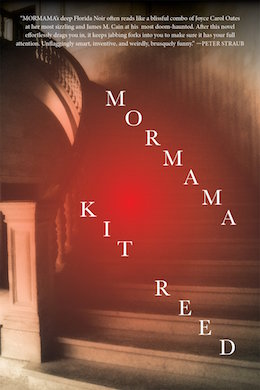

A riveting supernatural, southern gothic tale from Kit Reed, Mormama is available May 30th from Tor Books.

Chapter 1

Dell

“I happened to be in the neighborhood, so I thought I’d drop by.”

Not a line that gets you in the door no questions asked, Dell knows. Not on this street in this drab urban wasteland where the city swallowed the neighborhood whole and moved on, leaving a trail of ruined streets flanked by overgrown parking lots and tin sheds and mutilated houses—all but the one he is approaching.

He is here for a reason. When they returned his clothes the day the doctors cleared him, the pockets were empty except for this index card. It fell out of the sagging tweed jacket stuffed into the top of the plastic bag. It reads,

553 MAY STREET

JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA

It’s all he has of his past life. This and the flash drive. The thing slid out of his shoe while he was dressing, so sleek that his first instinct was to smash the object like a scorpion. Instead he shoved it into the jacket; he got dizzy looking at it, and it wasn’t just the head injury. He couldn’t throw it away; he couldn’t have it in his life. By the time it ate its way through the lining, he’d collected so much stuff that he had a dozen places to stash it. He needs to bury the damn thing.

Maybe here, at this address.

Something about 553 shouts, home, although it looms like a dowager queen waiting for him to explain himself. With its fluted columns and French windows coated with grit, the once white house looks like Tara, all used up and kicked to the curb. The row of trees to the right does nothing to hide the dented metal shed on the seedy parking lot that replaced another big house. To its left, a brick veneer front with combination windows hangs like a mask on an ex-mansion, with external fire escapes clamped on the sides to bring it up to code. A sign sunk in the green cement signifying lawn reads: marvista.

Apartments, boardinghouse or crack motel? He doesn’t know. Is this even the right neighborhood? He rubs the grit off a brass plate bolted to the gate in front of Tara here. It reads: 553 May Street, and underneath, Ellis. Reflexively, he fingers the frayed index card he’s carried ever since the doctors signed off on him and the cab company settled his bill. He left the hospital in clothes returned in the regulation plastic bag marked with his room number. The frayed tweed jacket, the shirt, the canvas boots looked strange to him. It’s all strange. The taxi that hit him knocked everything out of his head.

Fretting, he went through the pockets: no wallet, no ID, no glasses, just an unmarked envelope stuffed with small bills—payoff, he supposes—and this index card with the address in black ballpoint. He’s carried it for so long and studied it so closely that he doesn’t need to look.

Yep. This is the place.

Dell can’t tell you exactly why he’s at the Ellis family’s front gate. Unless he won’t. He is either a godsend or a threat to the women living in the house, and. This is bad. He doesn’t know which. The taxi knocked everything out of his head except the guilt.

Dell is not his real name. He grabbed this one off the wall like a hat off a hook. “Dell,” he told the others holed up in the gulch below the overpass where he bedded down when he reached Jacksonville. You don’t just walk in and put down your stuff without some kind of introduction. He liked the way it sounded. No last name. Dell was good enough for them. Look at it this way. Who, temporarily sleeping in a mess of cartons, wants to give up his particulars to guys who might give him up to the guys out looking for him.

“My name is Dell.” Dell what? To be determined. It’s past time to pick up a last name and put it on. No point scoring new ID until he can pay for that fake license, fake SSN, but still. He’s highly qualified, but he hasn’t had a real job since the accident. He used to be good at what he did. Tech, he thinks, but the details blurred somewhere between there and here. Situational amnesia?

Look. There are things a man needs to forget. He doesn’t really want to talk about the psychic train wreck that spilled him out here in the shadow of the interstate, where he showers at the Y as often as he can and takes care of the rest whenever. Not yet. Maybe the rest will come back to him when he penetrates this old ark.

If he really wants to know who he is, and that’s what bothers him.

Open the damn gate, stupid, go up on their fancy steamboat porch and knock on that door like a man, and when they ask you in, let them tell you what you’re doing here. Check out the interior through that beveled glass and work on your damn smile while you wait for them to come. Smile. Whoever you used to be, people liked you. Talk your way in.

Then what? Not sure.

Dell may not know why he’s here, but he spent weeks researching the occupants before he marched out today. The Ellis family owns 553. Have done ever since Dakin Ellis, the paterfamilias or whatever, broke ground in 1888 and built this heap for his new wife. It’s in all the city directories between then and now, and he checked every one. It gave him a sense of purpose. He moved on to a library PC with greasy keys, searched every Web reference to the family and followed up with visits to local historical societies, museums, decaying files in the belly of the Jacksonville Journal.

Procrastinating? Pretty much.

Jacksonville pioneers, the Ellises, one of the city’s first families, with too many men lost to notable accidents and untimely deaths. In its own way that’s creepy, and the creepiest thing? Their old world shifted and the neighborhood went from seedy to dangerous, but there are three old women still in the house like clueless passengers wondering why all the deck chairs are sliding downhill. He needs to get in there and find out what brought him to this old ark.

And he can’t get past the ornamental iron gate. It isn’t locked. It’s him.

Dell backs into the shade of their big live oak and considers. Scope the territory, he decides. Look for a way in and when you find it, leave. Let the rest come later.

It had damn well better!

He didn’t expect to be in Jacksonville this long. He slouched into this overgrown city months ago, looking to locate the address on this card and figure out what comes next. Instead he retreated into research, the perfect paradigm for what he is right now: all movement, no action. In late summer it was like walking the ocean bottom with the whole Atlantic on his back. Fall here was easy but in northern Florida, even winter is harder than he thought. It never snows, at least he doesn’t think it does, but it’s too cold to sleep in the elbow of the overpass. The other guys moved out weeks ago but until last night, he temporized. It was the first frost.

Even his teeth got cold. Whatever he has to do inside this old heap, he’d better get started. He enters through a gap in the hedge and darts for the ornamental shrubs below the long front porch with its grimy rockers and dead plants overflowing cement urns. The jumble of hibiscus and bougainvillea is so thick that a person coming out the front door might or might not hear something, but she won’t see him running along below. He rounds the corner and drops into a crouch, looking for a basement window. He won’t know that the first Dakin Ellis built this place like a plantation house in flood country, with an unbroken foundation: proof against high tides on the St. Johns River—in sinkhole territory, which Dakin didn’t know.

Safely behind the house, Dell steps away to study the back. A long porch runs the width of the house, with stairs coming down from the kitchen to ground level. The main business goes on above his head, on the sprawling first floor of the Ellis house. There are three rusty lawn chairs on the back porch, a weathered table and an old Kelvinator, leftover red wagon, ancient tricycle. Down here, lattice hides whatever goes on within.

Basement windows. Basement door, Dell supposes, with everything in him running ahead to winter. Openings just waiting to be cracked. He’ll find one where he can come and go without being seen and stake out a place. Then he waits. Until. The thought drops off a cliff. He can’t go there. Yet.

Feeling his way along the lattice, Dell moves into the long shadow of the back steps. Here. Hinges in the lattice at the point where the stairs intersect the porch. This part opens and shuts like a secret door. He raises the latch and ducks inside.

As he does, a scrap of Dante comes back to him: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.” For one riveting second, his blood stops running. Words drop into his head like ice cubes, Get out before it’s too late. What?

Hell with it! This new squat is everything he hoped. Big. He could roll in a Harley, if he had one. Furnish the place if he wanted, and they’d never know. Late afternoon sunlight slants in. He turns off his flash. He’s a spy, safe behind enemy lines.

Then why is every hair on the back of his neck standing up?

The place is dead clean. The floor is bald, as though enemies torched the crops and salted the earth before they moved on. There’s no door into the main basement that he can find; no damn windows! To his left, a cement rectangle spreads in front of cast-iron laundry sinks backed up to the brick foundation, with, yep, streaks of lime and rust. The faucets are still dripping, so, cool. His new squat may be cold but there’s running water here. He can bundle newspapers for insulation, lug in an extension cord long enough to reach the garage and Dumpster-dive for a space heater. Soon, when the December sun drops before 5 p.m., he’ll come back with his stuff and move in.

Stop temporizing, asshole.

Tonight.

Then he can take his time finding a guy who dupes driver’s licenses to document his identity: license and a Social. He’ll be DellSomething. Maybe his real name will come back to him. Is that a good thing? Probably not, but he’s sick of winging it. All he has is this index card. He forgets, but he can’t leave off grieving over whatever came down back then. Worse, he can’t bring back anything about it but this shit feeling of guilt that clings like tar that you rolled in on purpose. You can’t get it off.

He was probably fucked up before the taxi hit him, but when his skull broke, everything he knew leaked out into the street. Dell doesn’t know what he did or who he’s hiding from. It’s either selective amnesia or it isn’t. Split personality, maybe, good Dell/ bad Dell like the guy in that movie?

No. Dell is afraid of what he did. No. Of what he might do if they found out.

Whatever, here he is in Jacksonville, Florida, broke and temporarily homeless, with an uncertain welcome in the house above. At least he’s come to the right address, but he doesn’t know who wrote it on the card for him and stuffed it into the jacket. Or if it’s really his jacket.

Ignorant but hopeful, he’s here.

Dell squats in the gray Florida dirt, considering. He’s a decentlooking guy, he keeps himself neat. For all he knows, he has every right to walk into this house. He can walk in and they’ll know him. One of the old ladies will say. Will say…

OK, what? Thank God you’ve come? Hey, he could be the missing heir, a genuine Ellis whelp with a valid claim to some scrap of life here on May Street.

Unless, unlike Dell, they know what he did and they call the cops. They’ll double back on the—and the word smashes into him like an eighteen-wheeler—atrocity.

Atrocity?

Don’t go there. Think: prodigal son.

Unless you have… Dell snaps to, riveted. Special powers.

The lattice pops open. “Are you in there?”

He stands so fast that his head smacks a beam. “Holy crap!”

“Come out or I’ll call the cops.” It’s a kid.

Dell picks a splinter out of his forehead. Barks. “Building inspector, there’s an issue with the basement.”

A sound comes out of the kid: pfuh. “They don’t have fucking basements in Florida, I’m coming in.”

Make up some story, do it fast. “Hazmat issue, stay out!”

“Give up, asshole, I live here.” He’s inside, the arrogant little pest. Twelve, maybe. Sweet face for a garbage-mouth, scuzzy wild hair. Confrontational. “Who the fuck are you?”

They are more or less face-to-face here; he has to answer. “Dell.”

“Dell what?”

Think fast. “Duval,” Dell says. It is an inspiration. He adds, “Of the Jacksonville Duvals. I think we may be related, but I don’t want to bother them until I’m sure.” Questions chase each other across the kid’s face like an LED banner. Think fast. “Does your mom know you hang out down here?”

That face: yeah, she doesn’t. “She says it’s haunted.” “So you’d better beat it, right?”

“No shit. This ancestor Teddy got on fire down here back in the day. It took out half the porch before they got to him.”

It is not safe.

What? “You’d better go.”

No way. He has an audience. “Too late for this kid Teddy. Aunt Rosemary says he screamed forever but shiftless Vincent got to him too late.”

“Who?”

“Vincent. He was Biggie’s husband? She did all the wash. And the aunts are all, ‘Biggie could have put that fire out but no, she was upstairs in the kitchen, boiling water. Why didn’t the stupid girl run down and throw it on that fire?’ Down here they always blame black people.” He snorts. “But, shit! Berzillion years, and they still can’t let it go!”

“Who can’t?”

“The aunts.”

That would be Ivy Ellis, eighty-five, Rosemary Ellis Deering, eighty-one and Iris E. Worzecka, eighty-one, according to the new City Directory, City of Jacksonville: same girly names as the ones listed in the 1908 directory at this same address. Generations of sentimental Southerners, he supposes, passing down names like the family jewels.

“It happened right here where they poured the cement.”

“How do you know?”

“Aunt Ivy obsesses. She’s all instant replay, plus moral. Like, don’t play with matches, kids…”

Dell sighs. So they pass down stories too. “You should go.”

“She can’t help it, I guess.”

Overhead, a screen door slams. Dell’s gut clenches. “Hear that? They’re looking for you.”

There are no footsteps; just the sound of rubber wheels going back and forth on the boards above and a woman’s anxious, hollow shout, “Who’s down there?”

“I’m named for him. Is that creepy or what?”

“Teddy? Is that you?”

“Don’t call me Teddy!” He goes all guttural, whispering, “He was only three years old.”

“Better hurry.” Dell opens the hatch, as though that will make him go.

But the kid hangs in place, gnawing his knuckles. “Teddy’s fucking dead, lady. I’m Theo. Theo Hale.”

“Come on up here right now, you hear?”

Dell plays on their being in his secret place. “Quick, before she catches you.”

“No way, that’s just Aunt Ivy. She can’t.”

Ivy Ware Ellis, eighty-five. “That’s what you think.”

“She’ll never make it. Dakin Junior’s racking horse reared up and fell over backward on her, like forever ago. She’s a cripple, man.”

Ivy’s voice goes up a notch. “What are you doing down there, Teddy Hale?”

The kid gnaws his knuckles until he draws blood. “Fooling around in the dark with God knows who.”

Dell says, “Why are you so nervous?”

She cries, “It isn’t safe!”

The answer comes up like phlegm. “It’s a fucking trap!”

“This place?”

“The whole house. Look what happened to that kid!”

Dell nudges him toward the exit. “You should go.”

“Theodore Hale, you answer me!” On the porch the sound of wheels stops. She’s directly overhead.

“Beat it.” Dell is surprised by the thud of a gravity knife in his palm—his knife, he supposes, no blade showing, just the big bone handle. Thump.

“No way.”

“Really.” She’s so close that the base of Dell’s spine twitches. One flick and the knife turns deadly. “Go.”

“Fuck that.” Theo whirls on him, all spit and fury. “Your an- cestor didn’t burn up down here. You go.”

“Theodore Ellis Hale!!! Who’s down there?”

Thump. “Now.”

“Nobody, Aunt Ivy, OK?” Frantic, he repeats, “Three years old.”

“Come out before I send Vincent down after you.”

“They were all pissed at Vincent because he couldn’t get close enough to put the fire out. Like he was fucking stalling.”

She doesn’t exactly shriek. “Did you hear me?”

But the kid is in love with his recital. “And that’s not the worst thing that happened in this house.”

Go before I hurt you. Dell releases the blade with a snap. “Tcha!”

“OK, OK, but just so you know…” Shaken, the kid exits the hatch. After a two-second beat he sticks his head back in, all bloated and rasping like a demon in a bad movie. “This house is under a curse.”

Chapter 2

Theo Hale

In the dark, in this awful house, Mormama speaks to me. She comes in the night. When she’s in a good mood, she plants herself at the end of the bed and tells stories. Three suitcases and a steamer trunk, she says. Again. That’s all I had left in the world when I came to this house. Little Manette had all my grandchildren lined up on the porch to greet me. Dakin Junior and Randolph, Ivy and Everett, even the twins, everybody but the baby, and my daughter? She left Dakin to do the job, and do you know what my handsome son-in-law said to me?

I never ask. I don’t have to, she can’t stop telling it.

He said, children, this is your Mormama. One more Mama than we need.

She can’t stop telling it and I can’t get her to go away.

When she’s in a bad mood, she hangs in the air so close that it creeps me out and says shitty things. Boys are not welcome in this house. It isn’t safe!

And Mom thinks this tight little room is, like, sealed against whatever. She said so on our first night in this creaky old ark. At bedtime she took me up the big front stairs, all hahaha, like a tour guide. “Look at the panels, Theo. Solid mahogany. Your great-great-great Grandy spared no expense.”

“My what?”

“The first Dakin Ellis. That’s him on the landing in the big gold frame. Wait’ll you see your room!” It was just sad, her going,“Aren’t you excited?

Not really. Poor Lane, ever since Dad bailed you’ve been a mess, nailing hopes to the wall like circus posters, or pasting on fucking smileys that everyone hates because it’s so fake. Give it a rest, Mom. Just give it a rest. I know you’re bummed about moving in here with them.

But she doesn’t know that I know, so I make that belch where they think you answered, and they’re too embarrassed to go, “What?”

She, like, skipped on upstairs to the first landing, where the grandfather clock that the aunts fight over looms like a funny uncle, mwa haaaa. It bongs every fifteen minutes, obnoxious much? “Look!”

She was waiting for me to say I loved it. I said what you say. “OK.”

So she turned me around and pointed. From here it’s a straight shot down past the newel post with the shitty brass goddess of wisdom on top holding her light-up torch and on out that front door.

She said, “You can see everything from here,” like we’re in a museum and the exit is Exhibit A, and, me?

I studied it. Thick glass in the top half with a crap curtain hanging over it so you can’t see out the door, but above that there’s a wide glass transom, so you can. “Oh.”

Mom is all ta-daaa. “You can see who’s out there without them knowing. Theo, look!” Then, shit! She pushed the panel next to the clock. Booya. Secret door. “My room, after Mom got so sick that we had to move in here.”

That would be Poor Elena, according to the aunts, who talked about Poor Elena and all the other Elenas hanging from the family tree for, like, forever before Aunt Rosemary, who is either the Good Twin or the Bad Twin, depending on what she makes for dinner, said grace so we could eat.

“We were leaving as soon as she got well.”

Poor Mom. Shit happens to Lane, it just does. Her mother died upstairs in Sister’s room which is where they put Mom the night we moved in, and when I went, Who’s Sister, Aunt Rosemary was all, Don’t ask. They’ve been calling Mom Little Elena ever since we walked in even though she corrects them every time: as in, Elena was her mother. My mom is Lane.

Lane, trying to make me glad. “You get the best room in the house!”

Oh, Mom. Don’t try so hard! I went, “Great,” because it was so fucking sad.

It was this extra-big closet, pine paneled with brass fittings and a round window that opened and shut so I could pretend that I was on a boat. She stood there waiting for me to say, “cool,” but I couldn’t so she said, “The captain’s cabin. So you’re in charge.”

As if.

“Look!” She opened the porthole and made me hang out. Right, it’s too high for junkies to reach and too small to fit anybody but me, and Mom was prompting, like, “Repel all boarders, get it?”

Oh Mom, just leave.

“For when they fight.”

I just wanted her to stop talking.

“They’re all cute and excited because we just got here, but they’ve been in here together for too long. They fight, and when it gets really bad, watch out, they don’t care who they hurt.” I guess she couldn’t stop talking and I couldn’t stop her either, not the way she was. “This is the one safe place.” Then she sort of crashed. “Besides. She won’t come in here, she promised.”

I was supposed to ask her who. There was us and there was that clock ticking. Like everything else in the house had stopped. I thought, one of us has got to say something, but it won’t be me.

She said, “I was an orphan.”

Poor Lane. “You win.” I hugged her and she left.

See, her dad’s car crashed and exploded before she was old enough to know. She and poor Elena made it alone OK until cancer got her and they ended up here. After that it was just Lane and these fucking aunts, what are they, a thousand years old?

The ones that can still walk are the twins. Aunt Rosemary is the warden, quartermaster, whatever, kitchen police; don’t piss her off if you expect to eat. Aunt Iris is the general. I don’t know what her hair used to look like, but it’s gone all scouring pad on her, this extreme not-blond, with long black hairs that she doesn’t know about sticking out of her chin. Aunt Ivy is the crippled one. Excuse me. Disabled. She used to be an OK person, but everything changed after that horse rolled on her. She can go anywhere the scooter goes, she can even roll out on the back porch and make trouble for me, but tip that thing over and she’d flop around like a fish.

And my mom? She had to stay here after her mom died, and they never called her Lane. It was Little Elena, come here. Do this, do that, until she found the will. Turns out her dad was rich before he pissed it all away, how cool is that? After they had Mom, he did two things. So, did he have a premonition or what? See, he bought these bonds in her name. They’re in the bank down town. As soon she collects, we’re done with this creepy place.

The other thing her dad did was sign her up for boarding school, four years bought and paid for up front. So Mom escaped when she was fourteen. No more Little Elena. Get it? She took the train to Virginia all by herself and met the great big, scary headmistress of Chatham Hall with a great big grin. “Call me Lane.” She’s that smart. Done deal.

They helped her get a scholarship to FSU but she didn’t finish; she had me instead. She says she got so starved for family that she quit and married my dad so she could have one of her own. They were in love, but she swears I’m the only good thing that came out of it. So fuck you, Barry Hale, for wrecking the only real family we ever had, and fuck us ending up in this ginormous dump, stuck with the same old ladies going all “Little Elena” on her and, like Mom says, us fucking beholden to them.

That night she told me it’s just until she gets a job; she told me it wouldn’t take long and it will be a million miles from Jacksonville. She told me that this was my safe room. Look how that turned out.

That first night I turned the latch and put the pillow over my head but it didn’t shut them out, nothing does. I heard her and the aunts bonking around upstairs and after Mom stopped trying and went to bed I heard them yelling downstairs in Aunt Ivy’s room, which they did until the clock on the landing choked out eleven bongs and they all went to bed. On the eleventh bong the whole house shut down. By that time I had to pee, but it was dark out there and I was afraid to go upstairs to the bathroom, so I didn’t what you would call sleep.

It’s the house. It’s too old, like, nothing’s where you thought it would be, and it makes all these weird noises. Plus it smells bad, e.g. the blanket and this bedspread smell like mothballs and the sheets smell like feet and mildew and bad perfume, like ghost sheets ironed and put away by people that got old and died a hundred years ago, and on my first night in this room I lay there wide awake and blinking for, like, years.

Who could sleep?

I’d swear I didn’t sleep at all, except the next time I heard the clock was when it happened. It was dark as fuck inside my room, and I only counted three bongs.

The clock didn’t wake me up and it wasn’t having to pee, either. Around 1 a.m. I peed in my canteen because I wasn’t sleeping and I could hardly stand it and I guess I went unconscious, because then. Oh, fuck. Then.

It was the cold. With the furnace going and the blankets and the window closed, there was a difference. This weird chunk of air was in my room. I could feel this dense shaft of nothing by the bed, like a column of ice or an ice person. It wasn’t a draft, it wasn’t something breathing, either. It was like nothing you can imagine. It didn’t speak and it didn’t touch me. It didn’t come through the door or blow in on the wind. Nothing to see. It was just there.

I guess it was her, but I didn’t know it at the time.

But that was before Mom and me drove out to the Publix and we had The Talk.

About whatever it was. It wasn’t a thing, like, Thing. You know, from the movies. It was an object. I just lay there and waited for it to go away, although it didn’t blow out the door when I realized there was a presence. It didn’t speak either. It just stayed. It wasn’t like I went to sleep after that. It was more that I quit counting bongs and forgot time. Next time I heard the clock, I counted. It bonged eight times. It was light in the room and the cold, cold chunk of nothing was gone. I told myself, OK, it was a stupid dream. It had to be, because otherwise I was batshit crazy, and on top of everything that’s come down since Dad blew us off, crazy was one fucking thing too much.

Tuesday she was there again, but at the time I didn’t know it was her. I didn’t even know it was a person. I just knew it was way creepy, and this time made twice. I didn’t make it up or imagine it.

This happened.

The cold didn’t do anything, it didn’t say anything, it was just there for as long as it took to, like, make an impression? You’d think I’d freak with a chunk of black ice standing over me but it was OK. I thought I knew what the drill was. The sun would come up like it did yesterday and it would go away. Thing or not, I peed into my canteen like I do every night now, because no matter what’s in your room with you, you don’t want to go out there, ever, all by yourself in the dark.

I wash it out in the downstairs bathroom before anybody gets up. They fixed up the second-class sitting room for Aunt Ivy because of the scooter, but she has to wait for Aunt Iris to come downstairs and get her up.

It went on like that. Some nights she came. Others, I slept through, which was a relief. I didn’t tell anybody, because certain things aren’t real until you name them. Couldn’t see her, didn’t hear her, but I knew she would keep coming. I just felt it. Chunk of cold by the bed, solid as a post, but then it spoke to me.

Some of us are trapped here, blood of my blood.

At least I think it spoke.

Get out while you still can.

I didn’t know what it was, not then, and I wasn’t about to tell Mom, either. She has enough going on right now, between the aunts and snarky phone calls from Dad’s lawyers, plus, as long as I didn’t pin words to the wuddiyou say, presence, I could pretend it wasn’t happening. Maybe it would give up and go away. When that didn’t work I shook my fist at it and went, get out, and it didn’t say or do anything but THIS came into my head: I can’t, and that creeped me out, but I would die before I would bother Mom with it. Yeah, right.

This: Get out while you still can.

Excerpted from Mormama, copyright © 2017 by Kit Reed.